Interview with Pascale Gatzen: Fashion + Sustainability—Lines of Research Series

/by Mae Colburn

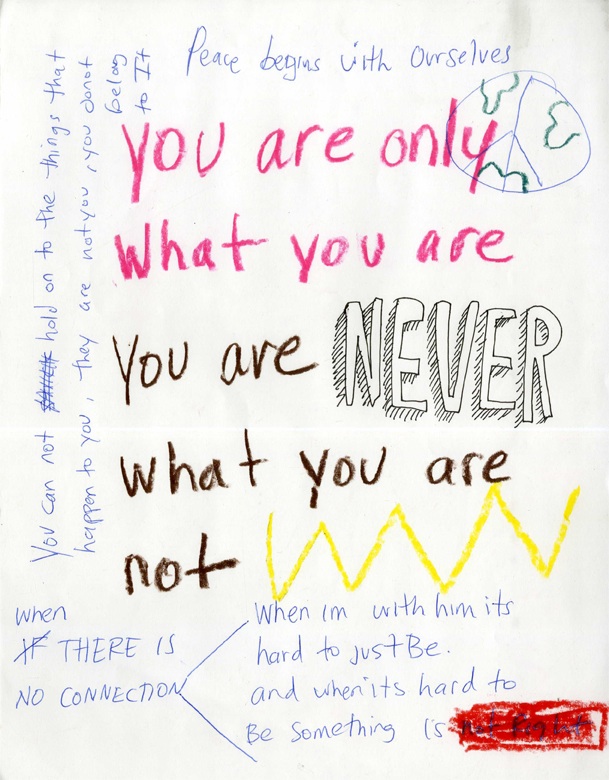

A student's response to Jean Luc Nancy's Being Singular Plural from Pascale Gatzen's class of the same name, Fall 2010.

Pascale Gatzen: Sustainability has to do with awareness, with love, with wellbeing, with the realization that we are creating this world together. It’s about exploring what we can be and who we can be, about connecting to a sense of play, pleasure, love, care, to a place where we value each other, where we see and are seen by others, and where we are willing to share, to be vulnerable, to be courageous.

Pascale Gatzen describes her position at Parsons' School of Design Strategies as that of a facilitator, nourishing “a productive flow of energy” between students. She isn’t interested in perpetuating disciplinary distinctions, social constructions, or the capitalist paradigm. She’s motivated by love, which for her involves movement, exchange, and relationships. Her logic stems from the realization, after years working in fashion and art, that creative production is too often motivated by insecurity and the need to prove oneself. Her focus now lies on the relational aspects of fashion, on alternative models of exchange. She describes student projects that include gifting, bartering, trading – models that explicitly forge a sense of proximity, immediacy, mutuality between people, between materials. For Gatzen, sustainable fashion is about nourishing a productive flow, motivated by love, of clothes, ideas, and identities.

Mae Colburn: You, and others, often use the words ‘love’ ‘play’ and ‘beauty’ to describe your practice. How did you develop this relationship to fashion?

PG: Growing up, I was interested in the idea of clothing, and fashion eventually became the focus of my education. I didn’t understand the notion of fashion practiced at that time. I didn’t see any real progress, or any movement. I didn’t see the difference between a shirt that was produced in one kind of cloth one season, and in another kind of cloth the second season. For me, they were the same shirt. I can’t say that my work was necessarily playful at that time, but I did at that time become aware that love was very important to me, that it brought me the most life energy, and that the closer I stayed to myself and to my own fascinations, the more vibrant my work would be.

Later, when I started teaching at Arnhem [ArtEZ, Hogeschool voor de Kunsten, Arnhem], I discovered that with the introduction of H&M and Zara, students had stopped touching their own clothes. There was this illusion that because they had access to fashionable clothes (which they could buy, because they were cheap), they were participating in fashion. So I started doing assignments with students that were very much about dressing. They had to dress themselves; they had to dress each other. They had to experiment with the notion of clothing, the power of dressing, which is a very vulnerable process. We have a lot of investment in how we dress and how we see ourselves, but something beautiful happens when we move beyond our comfort zones and everybody starts to feel vulnerable at the same time. Things become less absolute, less fixed, and people begin to feel a sense of play with their clothes and identities.

MC: On the Parsons' website, you're quoted as saying that you want students to “test the intersection between fashion and reality.” What do you mean by this?

PG: If I said ‘reality,’ I was probably referring to habituated reality. We live in this seemingly fixed reality, or at least we think we can trust certain things around us. With clothes, most people identify with a certain style, and they gain confidence from what they think they are and how they present themselves to the world. I did a workshop once where I compared the work of Coco Chanel to the work of Yves St. Laurent. If you really look at the work of Coco Chanel and see how it’s made – her attention to the make and finishing of the garment was amazing; how the lining was quilted into the jacket, the small metal chain against the back hem to weigh the jacket down, ever so lightly, the lack of interlining and shoulder pads, the way the sleeves fit into the body of the jacket allowing for movement and comfort – it’s very much about the person wearing the piece of clothing rather than the clothing as image, which is what I see on the catwalk and what Yves St. Laurent never escaped. Even if it’s an image of comfortable clothing, his clothing remains mostly image. Catherine Deneuve is quoted as saying that that you can wear Yves St. Laurent under any social situation because you’re protected, but I think Coco Chanel would say that clothing shouldn’t take up all the attention, that it should allow a woman to emerge as herself.

How do you engage the world? Do you engage in the world from a position of curiosity or do you engage in the world from a sense of fixed reality in which you have to protect yourself from everything that can happen? For me, of course, the first is more interesting and has a lot more potential for growth.

MC: Could you describe a workshop or project that you’ve done that encompasses these notions of curiosity, play, love – one that you’re particularly proud of?

I’ve done many projects and I always feel they’re very special. For instance, I worked one summer, as part of the Parsons' DEED project, in Guatemala, with five students and two artisan women’s cooperatives, Ajkem’a Loy’a and Barco in San Lucas Toliman. The beauty of that was being together for a month and seeing those students for who they are, completely. There was so much love between all of us. They were so focused – taking care of each other and taking care of me – and very responsible towards the work we were doing. There was a fullness of experience, of exchange.

That’s something that I also felt when I did an intensive program in DasArts, a post-graduate program in The Netherlands for theater and performing arts. They don’t have a fixed program; they have a sequence of different artists come in and do three-month intensive workshops with twelve students. We spent whole days together. We cooked together, ate together, and were living and learning together. I structured our days so that we did yoga together in the morning and had singing lessons three times a week. There was a real exchange of knowledge, of experiencing together, of going through rough moments and very amazing moments. I love the notion of life becoming part of teaching, teaching becoming part of life.

I also created a sequence of core classes, what is now known as the Fashion Area of Study in the Integrated Design program in Parsons, and the third core class, Love, is really about this, about students recognizing that fashion is not an isolated practice. It’s about integrating that practice in your everyday life, where they live, how they eat, and in exchanges with friends. That’s the most important thing I can imagine teaching to my students, and teaching with my students, because a lot of them just naturally understand these things. […] The traditional notion of learning involves a hierarchy between the teacher (who has the knowledge) and the student (who doesn’t have the knowledge). I think that’s the first assumption that we have to abolish if we want to grow a different type of world. Everybody possesses knowledge, which is of value to us all. I know knitting, I know sewing, I know patternmaking, but I’m much more interested in seeing students teach each other how to knit. If the students are teaching, then they understand that they have the ability to teach and grow and that’s what will support them when they’re out in the world. I think that’s the most important lesson: that they can always learn, always grow. And teaching and learning, growing are definitely not confined to the classroom.

A "singing blanket" that student Daniel Anesiadou made for a public event at DasArts in Amsterdam in spring 2005.

MC: What kind of theoretical background do you share with your students?

My teaching is very much about experience, but I do include some theory in class. Last semester I wanted my students to understand the capitalist paradigm, so we read Marx and Being Singular Plural by Jean Luc Nancy, and now we’re looking at Hannah Arendt. We read Erich Fromm, The Art of Loving, and we read The Gift by Lewis Hyde. We also read and look at the work of Sister Corita. Those are a few texts that I definitely use, but I don’t overwhelm them with theory. What I’ve learned in the past is that theory is more easily understood when there’s an experience to accompany the theory. The most successful theorists speak from a deep engagement with the world around them, and I think that’s very important.

Other people that are very influential to me – the way I think, teach, and practice – are people that I invite to teach. Susan Ciancolio is a very big inspiration for me. She has been teaching in the Fashion Area of Study for four years. I also have a very lively connection and exchange with Caroline Woolard, who teaches the barter class [at Parsons], and I’m very happy that Otto von Busch has joined our team. I’m very inspired by the people that I’m surrounded by.

MC: What do you hope to see your students to achieve in coming years, in fashion and beyond?

PG: At the moment, I think it’s about creating hybrid types of practices, hybrid types of life. Some of my students who graduated last year formed a business and living cooperative, building a business and growing their own food in a community garden nearby. If you support students in what they’re strong in, in what they want to do, they become more confident, more capable, more able to master their lives and make informed decisions.

I know from working, and many of my students know from working, that if you are really immersed in a dynamic relationship with your work, you will come up with unexpected insights that will result in unexpected outcomes. For me, it’s important that we constantly re-invent the forms that we engage with and relate to in order to give other possibilities for life. That’s what practice is about – constantly advancing the forms, because the forms are only ever temporary, limited, never sufficient for our ever-changing nature. We are always changing and always in a state of flux so we need to re-invent and continuously open up new possibilities for life to continue.

MC: What do you enjoy most about teaching?

PG: I love the exchange of collaboration, of growing together. I just think that cooperation is a much more natural way to live than practicing individually. It’s about care, and love, appreciating and respecting the things that we live with: the people, the objects, everything.

Pascale Gatzen is Associate Professor of the Body Garment Track at the School of Design Strategies at Parsons the New School for Design.

Mae Colburn is an independent textile researcher based in New York City.