Showmanship and History: An Interview with Harold Koda

/by Francesca Granata

Harold Koda, the eminent curator of costume who recently retired from the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute, moved to New York in 1974 to study the art of the Ivory Coast. In a sudden change of events, he instead ended up interning at the Met with the ulterior motive of becoming the protégé of the Costume Institute’s legendary Diana Vreeland while immersing himself in the fabled New York of Halston and Martha Graham. But before encountering Vreeland, who was away during the off-season, Koda landed in a socialite “sewing bee,” beginning what would be a lifetime devotion to the study and care of dress. Later, he joined the Edward C. Blum Design Laboratory (now the Museum) at the Fashion Institute of Technology as Associate Curator, before returning to the Met’s Costume Institute, ultimately as Curator in Charge.

At both the Met and FIT, Koda curated together with Richard Martin, working on exhibitions that brought together the showmanship he had learned from Vreeland and the historical accuracy he acquired through his painstaking study of objects. As Curator in Charge of the Met’s Costume Institute from 2000 through 2016, he oversaw the meteoritic rise of relevance—both in terms of audience and scholarly import—of fashion exhibitions. His exhibitions at the museum included “Extreme Beauty: The Body Transformed” (2001), “Poiret: King of Fashion” (2007), and “Charles James: Beyond Fashion” (2014). He stewarded the Costume Institute through a time of significant growth punctuated by the renovation of its galleries and 2011’s watershed exhibition “Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty” (curated by Andrew Bolton). I spoke to Koda in the living room of his tasteful Park Avenue apartment, opera music playing softly in the background.

Fashion Projects: Why did you come to New York originally? You didn’t necessarily move here to work in fashion curation.

Harold Koda: My personal story is relatively eccentric and idiosyncratic in terms of what happens now, because the field was just not as developed and did not require certification or background. It was much more open-ended. I feel like I am the last person who got into the castle before the gates were pulled up and everybody had to be vetted.

I came to New York to study African and Oceanic art at the Institute of Fine Arts. But when I got there, they said, “Primitive art? Robert Goldwater [the primitive art specialist] died two years ago!” I changed my advisor to Colin Eisler, who is a Renaissance expert. So I switched to Renaissance art.

But something happened in my second year. My best friend and I were supposed to go to Saint Thomas. At the last minute, I bailed on her for all kinds of complicated reasons. And then the plane crashed. She died. So that precipitates a really….You know, I was in my early 20s. I had never lost anyone who was so close to me. The guilt, because my friend had just changed the flight to accommodate my schedule…but then I couldn’t go. It was a very complicated, emotional time. For a year, I was really in a state of deep depression but paired with a wild carpe diem audacity. I was so sad, but it made me impulsive. I decided I am not an academic. I am really not interested in all this stuff. I don’t like poring over Renaissance reliquary. What I care about is what life is now. For me, that meant Martha Graham sitting with Halston and Liza Minnelli and Elizabeth Taylor and Tennessee Williams all in the same place. That, for me, was what New York was about and what I should aspire to immerse myself in. But I am inherently a conservative person; I am lazy but calculating. So I decided to shift my museum internship, and I told [my advisor] that I wanted to intern with Diana Vreeland. He thought it meant that I wanted to become a curator at the Costume Institute. But in the back of my head, what I was really thinking was, “I am so gifted”—this was the 23-year-old me—“that Mrs. Vreeland will see my gifts and think, ‘My God this young man is the next Issey Miyake!’” That was my thinking. I was throwing myself in front of Diana Vreeland so she could discover me.

FP: So you started interning at the Met?

HK: Yes, but my internship surprised me. Because I had heard that it was [with] Mrs. Vreeland—but it was actually with a curator in charge of the department, Stella Blum, and a marvelous woman named Elizabeth Lawrence, who was in charge of conservation. I didn’t realize that once the December show opened, Mrs. Vreeland disappeared until the following fall. So I was there in the Spring and there was no Mrs. Vreeland, instead I worked for Elizabeth Lawrence. The Costume Institute was very, very different then. It was all of these privileged women—there were a few Jewish women, but really it was all social register, married. Not explicitly racist, but clearly there were parameters. The Jewish women who were there were the WASPiest women you could imagine. It was like a country club. As I remember it, there were almost 60 of them, doing the restoration.

FP: Were these volunteer positions?

HK: Completely volunteer.

FP: So these were well-to-do women?

HK: Yes. There was this one woman who was so elegant and she was known for the way she could iron. This is a woman who probably never saw the back part of her apartment. But she would take a turn-of-the-century petticoat—which would have six layers of handkerchief linen and each layer had multiple ruffles, but if you even moved the linen it would crease—and iron every ruffle. It would just be pristine. It was like an Ann Hamilton art piece.

FP: Did you feel you were an outsider?

HK: No. Everybody accepted me very quickly. Because there were so many women, they were split up into groups. It was like a sewing bee, so there were 13 or 15 people a day in this work room. Stella’s first assignment for me was to dress an 1880s dress. I had never taken any patternmaking or sewing classes, which I think is really important, but Liz [Lawrence] realized that I was good with my hand.

FP: So you started out with the installation and dressing of mannequins?

HK: I was a very hands-on person. That was before I met Mrs. Vreeland.

FP: What happened then?

HK: In the fall someone named Stephen de Pietri, who later became the first curator of the Saint Laurent archive, came in and saw me working and dressing. In a way that was very Stephen, he said, “You think you are going to get a job here? You’ll never get a job—they never hire anyone!” And then he left. I thought, “What an asshole!” He ended up being a really close friend. But soon, I was hired to work on a show: “The Glory of Russian Costume” [1976]. The only reason I got hired was that the Russian curators did not want volunteers touching their garments, so for the first time they needed someone who was actually working for the museum. That’s how I got my first job.

FP: What was it like working with Diana Vreeland?

HK: She was really at her peak with the “The Glory of Russian Costume.” In the mid-’70s, she was going full bore. She seemed ancient to me, but I realize I am older now than she probably was then. She was really visual. She was verbal in a kind of fun fashion language way, but she could not really say, “I would like you to do this.” Instead it was, “Empress Sisi had a Hungarian lover who was a gypsy and she would wear her hair down with him in a tight rope like the tail of a horse with a postilion….” What!? The most fun part was that she would describe a mood or idea and then you had to actually materialize it into something.

FP: When did you first meet her?

HK: We had dressed all of these serf dresses, which were the wealthy peasants in Czarist Russia—those managing the land. And they dressed in a way that was different than the nobility in the city, who were wearing Western Francophile dresses. They wore traditional dress in the richest fabrics. We arranged them in the lower galleries and Mrs. Vreeland was coming in. You could hear her on the terrazzo because she had very heavy footfalls, and there were all these other young women who were her posse—the grandchildren of her friends, very social and privileged. They were coming in and she sees the serfs and she starts pointing and saying, “What is this? What is this? They have no auteur, no éclat.” And she snapped her fingers. They were exquisite. But she came down the stairs and kept saying, “No éclat, no auteur.” I don’t know why, it just irritated me. Nobody was speaking—they were just taking this bullshit. I said, “Excuse me, Mrs. Vreeland, but the Russian curators have said that the hems of the dresses should fall 6-to-8 inches from the ground because they were small women. That is why they are not 6 feet tall.” That is what she had meant, saying they had no presence—I was just addressing why they were small. She turned around and said, “Are you Japanese?” I said “yes” and she said, “Don’t you realize the Russians hate the Japanese? Always have and always will.” And then she walked off. And I thought, What a raving ass! For the first few weeks, I thought all she did was destructive. There would be a beautiful dress of demi-mourning and she would start to touch it and she would leave it like this poor woman had been ravaged. There were many people who met her who would just dismiss her because they would see that side of her. But if you really studied it, which I did, you would realize that she was seeing something that wasn’t quite apparent. It was perfectly fine, but it was not extraordinary. So when the mannequin was redressed, inevitably it improved.

FP: How long did you work with Mrs. Vreeland?

HK: I did four or five shows for her. She kept calling me back for special projects.

FP: So this must have been four or five years?

HK: Yes, but it is only for the duration of the preparation for the show. It starts in September, because that is when she was back, and went through December. It was very, very quick. I loved working on the shows and part of it was teasing out what it was that she wanted. She really had this marvelous way of telling a story. For instance, when I mentioned the Empress Sisi thing, really what she wanted was Hungarian coins made into earrings. It’s so ahistorical, but what she wanted to allude to was the rumor that Empress Elisabeth had an affair with a radical Hungarian national. What I learned from it is that objects have stories, and those stories are what are so compelling to the public.

FP: Do you feel there was a move toward being didactic in the museum experience of fashion?

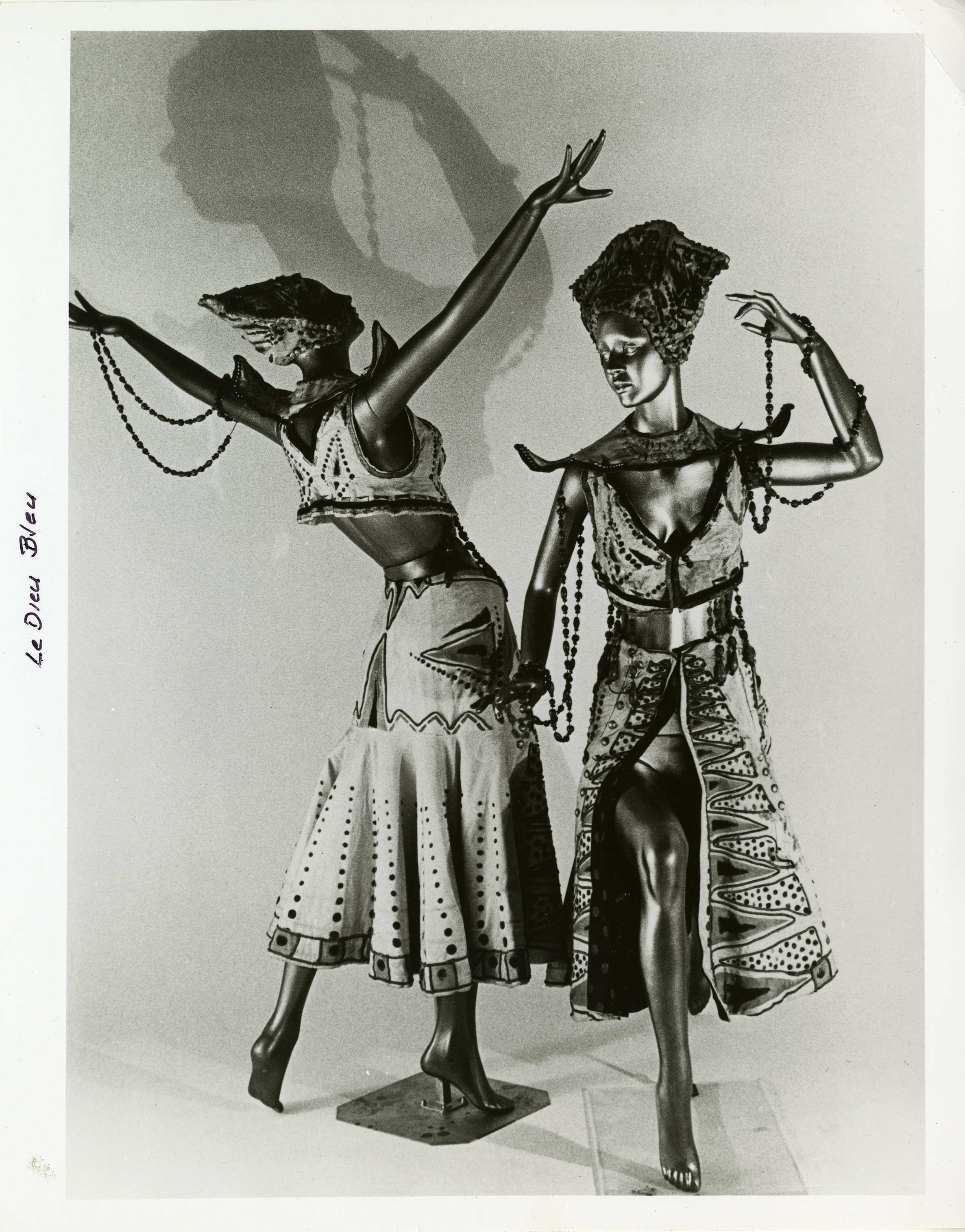

HK: Well, it had been didactic, and Mrs. Vreeland blew it out of the water. She was criticized for it by her contemporaries, but those were cries in the wilderness, because people really loved it. And the point that I learned from it is that you have to sell what you are doing. You can’t be passive. I remember working on the Diaghilev show [“Diaghilev: Costumes and Designs of the Ballets Russes,” 1978] under Mrs. Vreeland. We were working with a curator of Diaghilev’s costumes from the V&A. I said to him, “You’ll be astonished the first day the general public comes, because it will just be teeming.” He said, “Who wants that?”

FP: He wanted just an elite small audience.

HK: A privileged experience, not the democratic experience. Mrs. Vreeland was as elitist as it gets—but she liked the idea that if you were going to do something, it better blow your socks off and get you off the couch. The end game was how to make a subject seductive enough in the huge cacophony of cultural events in New York City.

FP: So you went from this experience with Diana Vreeland at the Met directly to curating at the Museum at FIT?

HK: It was 1979. Bob Riley was the director, but he needed a full curator. When I went for the interview, I was a dilettante. I had an art history background but nothing to do with fashion. I said to Riley, “For me, fashion history began in 1962 reading my mother’s Vogues and Harper’s Bazaars.” He said, “Well, at least you can read! Just read [Cecil Willett and Phillis] Cunnington.” The great good fortune that I had was that the collection had grown so much that it had to be edited. We were doing an assessment. I went literally through every piece of the collection with Bob Riley. And he was a terrible teacher and I had to be auto-didactic. For instance, we would take an 1870 bustle dress and then two days later we were taking out 1880s bustle dresses. Bob would say, “That is 1886.” And I would ask, “Why? How would you know immediately?” But he could not explain it, he would just say, “You just know.” So I started to examine it: The cut of the bodice is so different…if you looked, all the information was there. Now people who go into Costume Studies are not object-oriented. It seems to me a shame to go into curatorial practice and not care about the tangible object.

FP: So you learned costume history by editing the collection at FIT.

HK: That was my training: reading Cunnington and then going through every single piece in the FIT collection. So from Mrs. Vreeland I got the idea that with any exhibition you fail if you do not get people to see it, but unlike Mrs. Vreeland I wanted for it to be historically accurate. This was inspired by the Kyoto Costume Institute and what they did with historic costume. The Kyoto Costume Institute was called that because it is based on the Met’s Costume Institute, when Mrs. Vreeland was still working there. [Kyoto] took it a step further by keeping the panache, but getting rid of the ahistorical aspect. Once they set that model, we embraced it at FIT. You could still elicit an exciting visual response without getting into something that is not correct. It was basically merging Mrs. Vreeland and the Kyoto Costume Institute.

FP: In the early ’90s, you returned to the Met—you and Richard Martin left FIT to lead the Costume Institute. Your first show was “Infra-Apparel” [1993].

HK: With “Infra-Apparel,” it was sort of a template for something that even someone like Andrew [Bolton, the Costume Institute’s current Curator in Charge] is still doing. What Richard and I realized was that the demographic skews younger when it’s contemporary art—young audiences go to photography shows. It was clear that if you went to a Richard Avedon show, people looked young and sleek. It was surprisingly younger than if you went into a Rembrandt show. So to expand our audience we realized you had to have some contemporary hook. We always cared about the title, we always wanted to include something provocative and contemporary that established a linkage to art historical interest. With “Infra-Apparel,” we wanted to show that the chemise à la reine, which was so controversial when Marie Antoinette wore it because it looked like an underdress, had the same sort of potency as Gaultier’s halter for Madonna.

FP: So there was a parallel to bring the viewers to the past, to introduce the relevance of history to the viewer.

HK: The viewer comes because of the Madonna piece but then they are introduced to all these ideas: “Wait, it’s not something new—this kind of transgression and subversion of something possibly lurid percolating out into wearable attire, something intimate into something more formal. This has happened all throughout Western fashion.” Andrew does that a lot and it started because we realized that if you just do a show on 18th century apparel, you limit your audience.

FP: What was it like returning to the Met after being at FIT?

HK: Because it is a teaching institution with varied disciplines such as merchandising or graphic design, at FIT you could do anything. So we did shows about condoms, because that is dressing the penis. We did streetwear, the East Village….

FP: Did much of your work at FIT have to do with subcultures?

HK: Well, it could be about anything. “Fashion and Surrealism,” for instance, really brought our work to a larger public. “Three Women: Madeleine Vionnet, Claire McCardell, Rei Kawakubo” looked at designers that would be in any design collection. When I was a curator there, there was a gay illustration professor who died of AIDS and his surviving partner had a trunk of his clothes. He had kept clothing from when he was a student in the ’60s. He had a peace t-shirt that was done for the 1968 protest at Columbia, he had gay-clone things from the mid-’70s, all the way through the 1980s. So you had a gay person’s diarist representation of who he was, how he self-represented from when he was a late teen until he was a middle-aged man. It was this capsule of gay New York life. Gay culture now has become so diffused, but then it was so focused on certain tropes, at least dress-wise.

FP: And you acquired his wardrobe?

HK: Yes. It seemed to me that it belonged to the New-York Historical Society at the time or the Museum of the City of New York. But I wonder if any of them would take it. Everybody is focused on design rather than social history and we don’t do social history at the Costume Institute.

FP: When you went to the Met was it a big shift that the social history component was no longer there?

HK: It was more limiting coming to the Met—but they had all the stuff, the great works of art. You were in the context of an art museum, so there was the potential to collaborate.

FP: At some point in the ’90s, you left the Met—and fashion—to study landscape architecture at Harvard.

HK: I had done it for 17 years and I wanted to experience another thing. I wanted something that was interdisciplinary—and landscape architecture was just that. A little ecology, a little engineering, lots of aesthetics.

FP: But before long, the Met got you back.

HK: When I left, Richard was well. By the second year I was in school, I realized he was seriously ill—he had melanoma—and in the third year he died. Richard actually asked me to come back. I told him no—the only reason I stayed so long was because it was exciting for me to work with him. So why would I want to replace him? But Philippe [de Montebello, then the Met’s director] kept calling and asked me to vet the finalists for the position. They were all so different and brought different strengths and so I told him, “Philippe, you really have to decide.” And one day he called and asked what to do about deaccessioning [part of] the collection. Up until then I had been completely dispassionate, but as soon as he said that I was so shocked. I said, “Philippe, there are international standards to do this, but it is a very subjective process. You shouldn’t be talking about it with me—you should hear what each candidate has to say.” And he said, “Harold, you sound really upset! Would you consider doing it?” So we met and he offered me the job. I said I would take it with the idea that I would leave in three years. I could get the process started and I would secure a team. But then 9/11 happened—planning to stay three years, I stayed 17 years. Later I told Philippe, “You were so 18th century French and devious to do that.”

FP: Your goal was to complete the assessment and partial deaccessioning project?

HK: Yes—it was not my ambition to do shows. I am a believer in shelf life. Even Mrs. Vreeland by the end, she had a signature. But if you want vigorous interpretation of something, you need a fresh perspective.

FP: And yet your time as Curator in Charge at the Met saw the elevation of the field of fashion curation.

HK: So much of my career has been extraordinary good fortune. As Philippe would say, you have a trifecta at the Costume Institute: There is you and Andrew, there is the collection, and there is Anna Wintour, who was our rainmaker. As for the Anna Wintour part, we always fought against the external perception that she was generating the shows and that it was always predicated on some commercial [concerns]. There is a slight truth to the fact that she would influence our calendar. Like with “Goddess,” it was very hard for her to find a sponsor, so we had to defer it a little bit. But she never said, “Don’t do it.” She just needed time to support us. And if we didn’t have her there would be no Costume Institute, because with costume you need exhibition furniture, you need all the mannequins. To do it properly is extremely costly. We were able to do it because of Anna’s support and all of our sponsors. None of what we accomplished could have been done with money. And that is really part of the triangle: great collection, adventurous curators, and someone who can support their ideas. It was a really fortunate thing—a convergence of elements.

FP: At the same time, did having Anna Wintour and the party of the year put a lot of pressure on you to do innovative exhibitions every single year that could sustain the level of scrutiny?

HK: It’s really good to have somebody with the Taser. Some of the people who attend the party parachute in—they’re clueless—but the interest it generates in the show is fantastic. We want people to be engaged in what we do. We consider a failure if it is just 200,000 visitors. If we did no advertising, if there was no party of the year, we could get 900 to 1,200 people a day. In the general audience there are enough people who are interested in our shows. But we want 2,000 or in some cases 5,000 people a day. And those seem like very crass quantities to aspire to. But if you don’t quantify, you have no way of measuring your success.

FP: In the long span of your career, how do you think the field has changed?

HK: The general public is much more informed. There is a general level of expertise that has been heightened. With the proliferation of many more museums, there is also the requirement to have a distinctive voice. You have to up your game. But that’s a good thing. I don’t think there is ever going to be a surfeit of costume exhibitions. The bad thing would be if all of them are mediocre.

FP: Are you afraid that object-based knowledge is going away?

HK: Connoisseurship is out the window. Costume and textiles people have a problem of access. I was the last one before the drawbridge pulled up. I was very lucky to go through the collection. It isn’t bragging, but just because I have done it for so long, I can look and say, “This isn’t right—the proportion is wrong, it’s been hemmed.” And that’s connoisseurship.

Fashion Projects editor Francesca Granata, Ph.D., is Assistant Professor of Fashion Studies at Parsons School of Design and the author of the book Experimental Fashion: Performance Art, Carnival and the Grotesque Body (I.B. Tauris, 2017). She was a research fellow at the Met’s Costume Institute in 2007–2008.