Interview with Sass Brown: Fashion + Sustainability – Lines of Research Series

/by Mae Colburn

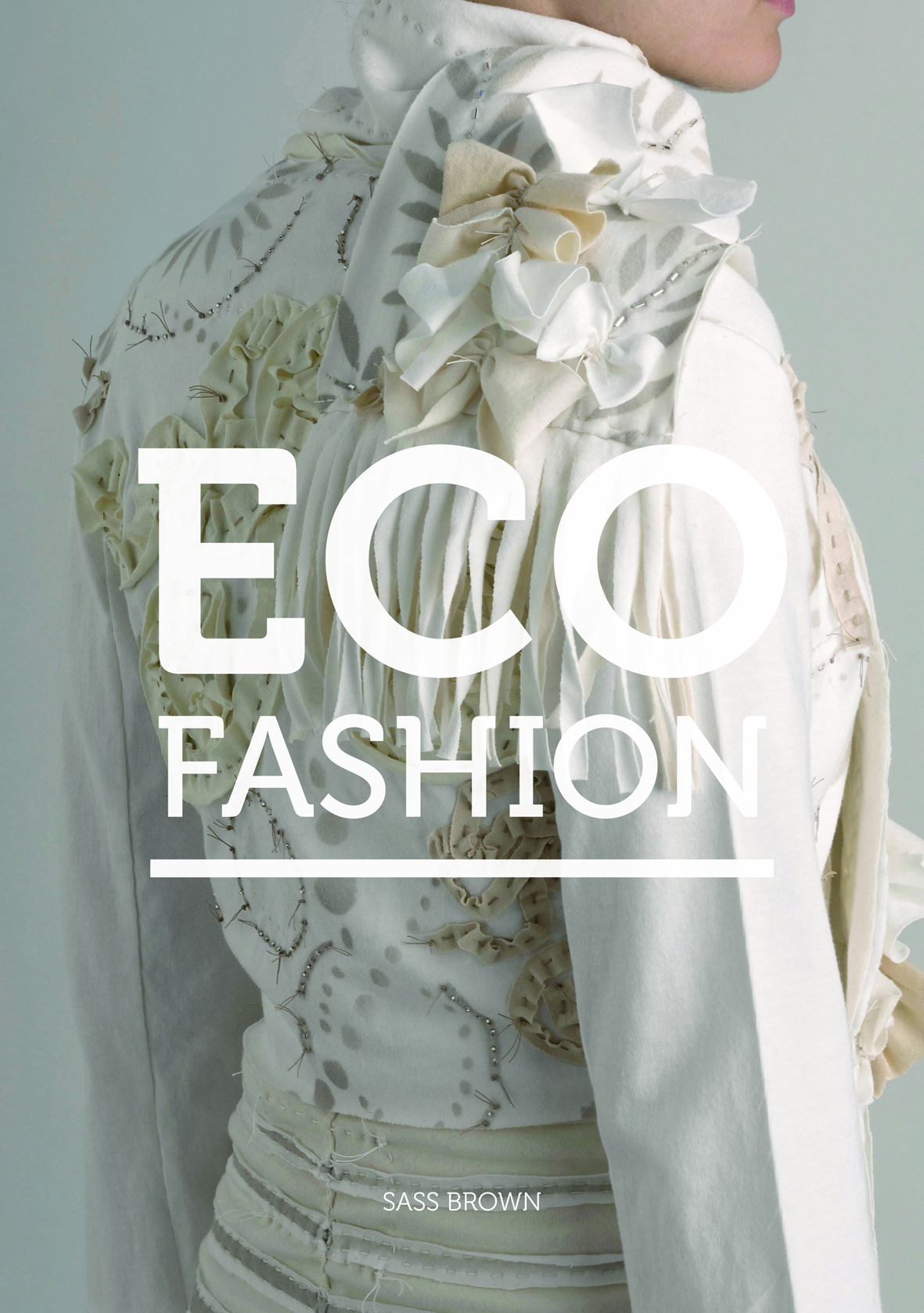

Sass Brown's first book, Eco Fashion, published by Laurence King Publishers in 2010.

Sass Brown's first book, Eco Fashion, published by Laurence King Publishers in 2010.

Sass Brown likens her work to that of a fashion curator, one that looks beyond aesthetics and into the realm of ethics and ideas. Her book, website, and blog feature designers from around the globe who unite fashion and ecology in thoughtful, innovative ways. Brown entered this line of inquiry after years working as a designer in mainstream fashion, a background that gives her a unique perspective on the distinct qualities, and currency of ecological ideas within the fashion sector and valuable insight into the role of fashion education within the broader global information network that supports, and defines sustainable fashion today.

Mae Colburn: To begin, how do you interpret this word – sustainability?

Sass Brown: Well, sustainability has a defined meaning that you can look up in the dictionary: not depleting, not polluting, not taking away what you can’t get back. Where it gets muddy is when you start putting it in different silos such as sustainable fashion or sustainable lifestyles – that’s where it starts to get more interpretive and where words like eco or green are much more broadly used because they have less defined meanings.

MC: I’m sure this thought process informed the title of your first book, Eco Fashion.

SB: (laughs) To some extent, yes. I actually wanted it to be called Sustainable Fashion but my publishers fought me on that one because they felt that sustainability wasn’t a completely understood term. Plus, my publisher is British, but [the book] was distributed in the U.S. and also translated into Italian and Spanish, so they felt eco was an easier term for people to grasp on to, and in fact it’s actually more correct than my initial title.

MC: Both your book and your website highlight the work of a wide variety of designers working in eco fashion. How do you go about conducting your research?

SB: Well, when I first started this research years ago, one of the nicest surprises was that eco designers would give me all of the contact information for their biggest competitors, because they supported them, too. It’s a very collaborative industry. […] People want to share because they believe in the development this area of design – and that’s dependent upon all of us understanding and knowing and sharing resources. It’s not like the mainstream fashion industry where everybody jealously guards their contacts and knowledge.

A screen shot from Sass Brown's website.

A screen shot from Sass Brown's website.

MC: You research and write, but you also lecture and teach workshops on fashion and sustainability. Could you elaborate on the role of information sharing within this movement, and specifically your own role in shaping this dialogue?

SB: I think information sharing is absolutely vital and that my role, or what I see as my role, is to research, share, and collaborate on that information. Designers in the industry and students who are currently studying to graduate and move into the industry need to see concrete examples of what is being done, how it’s being done, and who is doing it. I focus equally on fashion as I do on ecology. I’m not interested in writing about the next beige t-shirt – whether it’s being produced ecologically, fair trade, or what. There are enough people already doing that. Fashion is a world of inspiration and aspiration and I think it’s incredibly valuable to inspire designers about what’s possible. One of the best ways of doing that is showing some of the best aesthetic examples of what’s being done with sustainability, ecology, and design.

I’ve been described as a curator by several people and that’s probably more accurate than anything because I really am curating already existing content rather than developing my own; I might be rewording and rewriting and collating it in different ways, but I'm working with things that have already being done. I think that’s actually quite a good description of what I do, especially in certain digital media like Facebook, or Twitter, or Pinterest, or StumbleUpon, or any number of other areas. It really is about collating and collecting and disseminating.

MC: This is something I’ve thought about quite a bit – this question of how specialized knowledge about production, consumption, and so on, can be translated to a broader public in a way that seems relevant.

SB: Well, I think most of the issue is that most of the specialized information comes from activistic circles and is accessed by those who are interested, as opposed to being disseminated to everyone whether they’re interested or not. It hasn’t gotten to a level where the average person on the street is aware of Labour Behind the Label or the Clean Clothes Campaign, or any number of other advocacy bodies who police or certify the fair trade or sustainability of our industry. Digital media and blogs are beginning to bridge the gap, whether it’s my blog or blogs like EcoSalon or Ecouterre, which aim for a more fun, cool, interesting notion of ecology as opposed to a grassroots, hardcore, tree-hugging ecology, which I think is still very foreign to a lot of people and off-putting in a lot of cases.

MC: Do you have any last thoughts about education, information sharing, and sustainability?

SB: As I said, I think that having multiple channels is really important, whether it’s the structured educational field through curriculum and classes, or personally-motivated websites and blogs, or activistic and certification bodies who really get down to the nitty-gritty of who is doing what, how, when, and where. I think it’s really vital that there are lots of different perspectives and different voices. That’s the only way we can reach the broad variety of people out there. It’s never one-size-fits-all.

Sass Brown is Acting Assistant Dean for the School of Art and Design at F.I.T. and former Director of F.I.T.’s study abroad program in Florence.

Mae Colburn is an independent textile researcher based in New York City.