This is Not A Fashion Critic: An Interview with Guy Trebay

/by Jay Ruttenberg

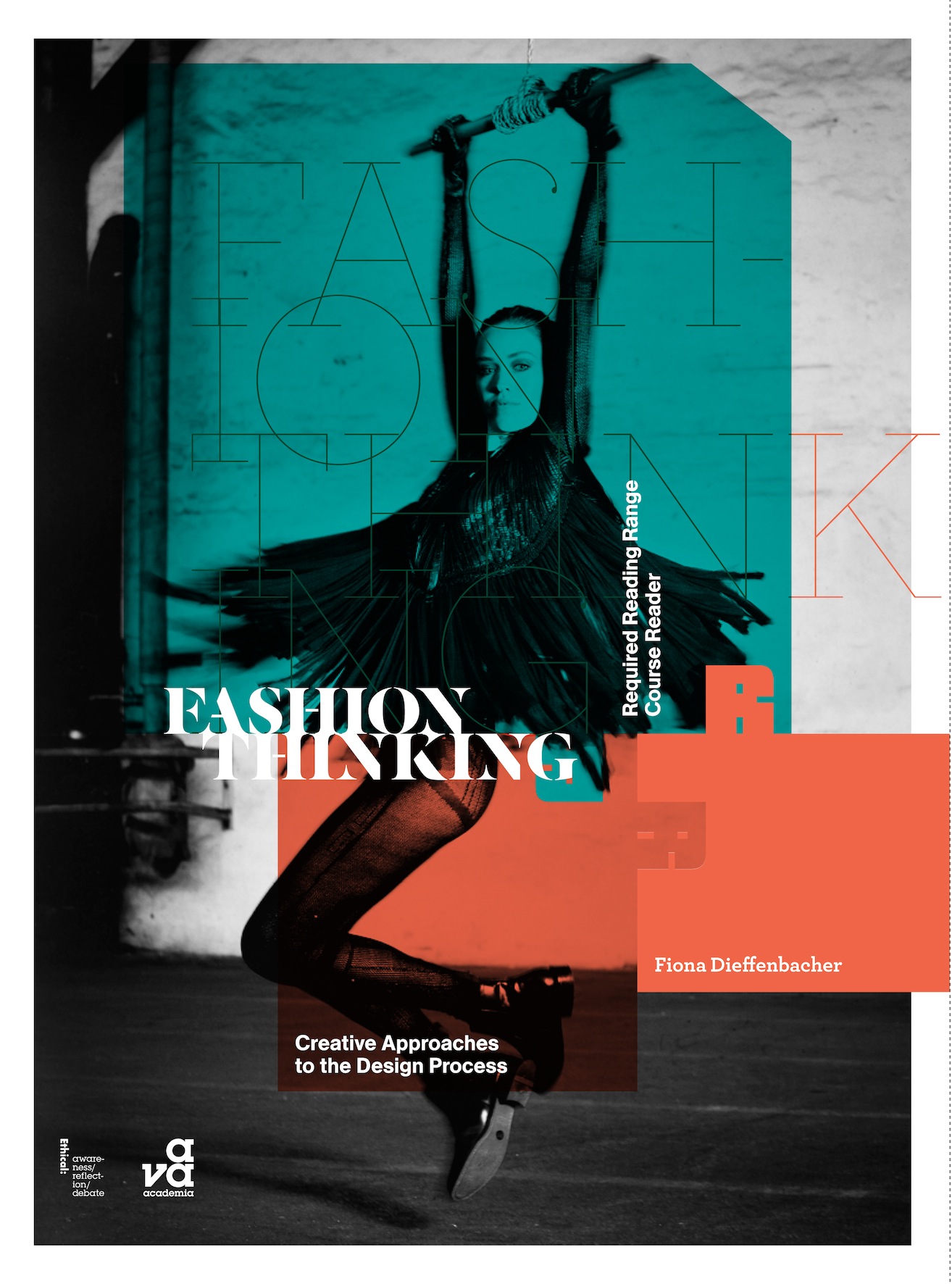

Illustration by Nathan Gelgud

Guy Trebay, of the New York Times, defines himself as a cultural critic and even when working the traditional fashion beat, allows his attention to wander into that broader realm. Although he operates without a column, Trebay’s articles are easy to spot. Like some debonair newsman of Hollywood lore, he reports from exotic corners of the globe. He is cynical without being closed-minded or small, and writes about glamour with neither aspirational veneration nor wanton bloodlust. His writing on style betrays a love for the fashion world, yet he does not hesitate to shiv those who have it coming. Most conspicuously, his every sentence is spun with a panache that seems perhaps too opulent for newsprint, even that of the Times. “The lush mane was ratted and back-combed into a frowsy beehive, the kind in which hoodlums of legend used to conceal their razor blades,” he wrote about Amy Winehouse shortly after her death. “Her basic eyeliner became an ornate volute, a swath of clown makeup, a cat mask.”

Prior to landing at the Times’ Sunday Styles section, in 2000, Trebay spent two decades at the Village Voice. Where his current post finds him traipsing between Miami art parties and Milan menswear shows, his Voice column—anthologized in the 1994 book In the Place To Be: Guy Trebay’s New York (Temple University Press)—sent the writer to more humble quarters, often up in the Bronx. If his change of landscape follows the New York zeitgeist, Trebay’s history also lends his fashion writing an unavoidable socioeconomic undertone. “Once it starts to be just about clothes,” he says, “I’m out.”

Trebay met Fashion Projects in a small conference room at the New York Times building, sandwiching the interview between reporting trips to Europe and Los Angeles.

Fashion Projects: You’ve said that you don’t consider yourself a fashion critic, but a cultural critic.

Guy Trebay: That’s right. First of all, what is a fashion critic? What is that? I mean, it’s not a very developed critical discipline. It seems to me that for decades, it was a kind of business reporting. But somewhere along the line, in a very wholesome way, it evolved into getting some critical discipline. I guess it’s like movies. In the beginning, there were no movie critics. At a certain point in our period, fashion developed something of the valence, culturally, that movies had.

FP: When?

GT: I’d guess the ’80s, but I really don’t know. When I first started writing about this, it was in a much broader context. I was writing about the city for the Village Voice—I wasn’t writing about fashion, per say. But fashion shows would come to town like the circus, and it would change the atmosphere of the streets. You were aware that there was this population of people coming in from who knew where, and models like gazelles were leaping over sidewalks. And you were like, “Well, this is interesting.” But in those days, it was a small and very contained world. The knowledge wasn’t widely dispersed. That has changed so radically. I came to the Times in 2000 and by then, IMG had gotten into the business. IMG was a sports promotion company, as everybody knows. But Mark McCormack, the founder, looked at the landscape and said, “Where am I gonna find another thing that is as translatable across cultures and—without the necessity for language comprehension—can sell as an image language. That’s when they got heavily into fashion and started these fashion weeks. They bought into New York Fashion Week and it became this global plague of fashion weeks.

FP: Before that was it simply an industry event? GT: It was a trade week. For all that I’ve poked fun at the proliferation of fashion week—the Bulgarian Fashion Week and whatnot—it’s very useful. There’s a circuit that people routinely follow in this business: New York, London, Milan, and Paris. Over time, people have talked about how it can all be done online, but that absolutely isn’t the case. The longer I’ve been around it, the more I’ve become aware of the way that information is transmitted through the tribes or the pack. It’s quite beautiful, actually.

FP: Why do you think it couldn’t work online?

GT: The same with everything else that has to do with person-to-person contact. It’s over mediated. For all that it’s so global, it’s pretty hermetic. Particularly with fashion, a lot of the cues, being visual, are too subtle.

FP: Do you mean not being able to see the texture of garments in fashion week slideshows?

GT: No, I think those are great. But I’ve always been interested in the sociology. And that’s a little more opaque online, which is more garment-based. Also, there’s another thing that happens online, which is the super narrativization around sites like the Sartorialist. That’s a very editorialized site. It’s one guy’s idea of what some kinds of people look like or should look like. It’s very successfully put across. But at the same time, when I look at the Sartorialist, I’m much less struck by the clothes—or whatever people think they are putting across with the clothes—than by the strings. The degree to which people want to create narrative around you based on a picture of you and your clothes is very compelling to me. People are telling themselves stories about other people based on the way they tie a scarf. Which we probably do in real life, but it has a little more practical utility in real-time encounters than it does online. There’s a little whistling in the dark happening, where everybody’s telling themselves a story that doesn’t really have to do with the other. And fashion is about the other—you require social interaction for it to get off the ground. [Pauses] God, I hate those.

FP: Tape recorders?

GT: Yeah. I never use them. When I was a kid, I wrote for Andy Warhol’s Interview

FP: Well, you must have used one there.

GT: No! Can you believe it? At first I did. This was like the dawn of time—the center of the earth cooled, and Andy started [the magazine]. And I was working there—I was, like, 19. Somehow, I had forgotten to finish high school. I did an interview with Christopher Isherwood. I tape recorded it and then my mom very helpfully typed it up, because I couldn’t type as fast as her. He had a very grating voice. When she transcribed the thing, it was almost like out of a John Waters movie, where the person throws a typewriter out the window and runs screaming from the house. I thought, Maybe I won’t use this tool anymore—it drives a very patient mother crazy.

FP: How old were you when you left high school?

GT: About 17. I mean, I just dropped out.

FP: You grew up in New York, right?

GT: My parents had an apartment here, but I basically grew up on Long Island. But by the time I left high school, most of my life was already here. In those days, I wanted to be a painter. So I came here and got an apprenticeship. I started painting and making videos. And I wrote plays. I’m not sure exactly why, but they were produced at WPA. In a world that no longer exists, you could kind of have that life.

FP: Did you get introduced to journalism through Interview?

GT: I backed into it through Interview. I went on to be their so-called Paris correspondent for a year. I was 19, maybe 20.

FP: Did you know Warhol?

GT: I knew Andy, but I can’t say I was an intimate of his.

FP: That must have been amazingly intimidating. GT: No.

FP: You were a teenager, hanging around the Warhol crowd. How was that not intimidating?

GT: It wasn’t an intimidating scene. I know that sounds weird. I think people have trouble understanding it because of the mythologizing of him, which is so extensive now. But the fact that Valerie Solanas could walk in there and shoot him speaks to how porous that world—and all the worlds in New York—were at the time. You could get in. In New York now, I don’t think it’s about how easy it is for you to get in. Anywhere.

FP: When did you start working at the Village Voice?

GT: Late ’70s, around the same time that Jim Wolcott went there.

FP: That must have been one of the newspaper’s real golden periods.

GT: I can say it was. It affiliates itself very naturally in my mind with the problems that I have with the general cultural relation to Occupy Wall Street. Of course people feel like it’s nothing and they have no goal: Nobody knows what a counterculture is [anymore].

FP: Your subjects at the Voice differed from your Times work. What was the thrust of your Voice column?

GT: I think I did the column for 20 years. I don’t know how you can characterize it. It was urban anthropology, maybe. The thing is, I was just going out and reporting on stuff that the mainstream media hadn’t gotten to. It sounds very self-aggrandizing to say this now. But I was talking to a friend the other day about having been in the Bronx project houses with [Africa] Bambaataa. And ABC No Rio, the Times Square Show, and also a lot of gay culture…there was a lot of emergent culture. There was a lot to write about. It would just be the normal part of what you would be reporting.

FP: In the Place To Be, your book collecting many of those columns, focuses a lot on the Bronx. Were you living there at the time? GT: No. Although when I worked for Andy, I did live in the Bronx. I’m kind of a Bronx nut. I just like the Bronx. I did some really early stuff about crack, which came after I was brought to meet the mother-in-law of Eric B., of Eric B. and Rakim. She lived in a certain housing project. She was a hard-working woman, and her life was being destroyed—as many people’s lives were—by crack all around her. I was really compelled by that, and went back and back and back.

FP: In the introduction to your book, you write about how the unhinged New York of that period differed from the buttoned-up town of your youth. It’s funny reading that now, when so much nostalgia is essentially the opposite—today’s New York being sedate compared to the wild city of the ’70s and ’80s. GT: There’s a definite arch. I’m not a fan of nostalgia at all. But I don’t think my memory is falsifying to say it was a very yeasty period. Maybe not to everybody’s taste, and there were plenty of problems. But as I said, there was a porosity, culturally, that has been replaced by a kind of cultural paucity. You could move in and out of worlds.

FP: But weren’t you able to do that easier because you were a reporter?

GT: No, no, no. I always looked preppy, and people used to say to me, “Oh, you go [to the Bronx]—it’s so scary.” But as long as I was respectful to people, I was treated respectfully. In my experience, the city had a greater degree of openness. There was a mixture of uptown/downtown that’s gone out for real estate reasons—as usual. We all know that there’s a general trend to cultural conservatism. At the same time, everybody essentially got remarginilized.

FP: When did you join the Times? GT: In 2000. I came to the Styles section. I kind of morphed into doing more fashion as I came here. It was at a moment when fashion was really emerging as a cultural force.

FP: Was it strange to go from writing about the Bronx’s crack problem to fashion shows?GT: In a way—except not if you’re inside my head. I’ve always had these interests. I was talking about this with Judith Thurman. We were pissing and moaning, as people do who have an interest in these degraded subject matters and culturally disfavored subjects. She was talking about a certain correspondent for the New Yorker who writes about child soldiers in wherever. She was saying that that kind of thing—if you have the skills, the stomach for the work, and can stand all the risk—is like taking gold out of streams with your hand. It’s all there. There is something slightly perverse and masochistic about applying yourself to [fashion] and having to rehabilitate things that are considered culturally beneath regard. That’s been the most challenging part of this for me. Because it isn’t taken seriously, and never has been taken seriously. I hope to live to see the day when it is. Which can be done without sacrificing what’s beautiful and delightful about the ephemeral and frivolous part of it. Those are not opposing ideas.

FP: Do you think the disparagement comes from the tradition of fashion being in the women’s section of the paper?

GT: Of course. It’s women’s work. It’s feminine, it’s not worthy of masculine attention and regard. [When I started here], people said, “You’re throwing your career in the toilet to write about fashion.” Not that it’s such a big career.

FP: Oh, please. But do you think they would say that now?

GT: They may well.

FP: But you did say you noticed a cultural change in the last few years.

GT: The culture changed. I think people are interested in [fashion]. I was a contract writer at the New Yorker for quite a long time, paralleling the Voice thing, and I wrote for lots and lots of magazines. You never saw anyone in those mainstreamy magazines writing about fashion. I mean, Kennedy Fraser and then Holly Brubach did [at the New Yorker], but it was pretty much about the collections or the occasional profile. They didn’t have a style issue at the New Yorker. It wasn’t what we serious people—that is, people with testicles—do.

FP: Do you think that fashion writing needs a Pauline Kael? GT: I don’t know what fashion writing needs, frankly. It’s not one of my main concerns. I think writing just needs better writers, period. I could hope for the liveliness of Pauline Kael—kind of crack-brained opinion-slinging. Remembering back to the Voice, and that whole auteur/anti-auteur world, it was so micro, but so essential to groups of New Yorkers. That conversation is long gone. I haven’t encountered tons of people dissecting fashion writing. It’s pretty much been hijacked by the visuals, as it probably ought to be.

FP: In many ways, is fashion writing most similar to sports writing?

GT: That’s probably the closest analogy, yes. It’s specialist. I read the sports section very, very avidly. It’s one of the few places left where you find human interest. It’s very narrative, not to say novelistic, to follow sports teams and sports in play. Fashion is a bit like that, because the personnel set is not that changeable. It’s one of the weirdest and most contradictory things about fashion. It’s based on novelty, but in many ways very little is new. It’s such a stable population. All the editors have been the same forever. All the designers have been more or less the same forever. The only thing that changed was when Anna Wintour saw that nobody was developing a farm team, and got in gear. Because everybody was aging out and there was nobody to replace them. Because she’s a great HR person, she literally made it her business to make another generation to cultivate and anoint.

FP: Why do you think fashion is so stable? GT: It’s a very conservative business. And it is a business. [In the past], the city could support somebody who didn’t get into the business with a business plan and a backer. You can no longer do that—that’s out. You better arrive with a business plan and maybe an MBA and, whatever your design skills are, hope that Anna Wintour will take you up.

FP: Do you think that fashion from New York designers has suffered?

GT: I don’t know. I think there are a lot of people who do what they’re meant to do here. It’s a commercial center. It’s hard for me to pronounce on this, because I don’t know if my lack of interest in what’s going on in New York—across the board, culturally—is my problem or New York’s problem.

FP: Do you still cover the shows in Europe?

GT: Yeah, though not as much as before. I’m mainly writing about menswear. I’ve [always been] more interested in menswear. When I started, I felt like there were more ideas in play in menswear. Masculinity was much more up for grabs. There was a lot of gender play, when I started.

FP: You mean when you started at the Times? GT: Yeah. When I got involved with this as a full-time thing, there was a lot of change. It was a bracketed period. I didn’t realize it at the time. Starting around 2000, the multinationals saw what was happening. They realized that this was really gonna blow up—that this fashion thing that had been niche and not fully exploited could be globalized. And they invested heavily. Three of these multinationals—LVMH, PPR, and the Richemont Group—got heavily into reviving old marks and houses, then buying and creating stars, [in order] to put this thing across globally. We were all beneficiaries of that. That’s how Alexander McQueen happened. That post-mortem show at the Met, which had these staggering 600,000 visitor numbers, was a tombstone for an era in this business. Galliano being discredited, McQueen being dead, Tom Ford having morphed into whatever he has morphed into…. These were all showmen who were heavily funded by multinationals. Now, the multinationals have gotten what they were after, and there isn’t so much need for [showmen]. You don’t need the showpieces anymore—the marks themselves do the work. We’re in a new era. All the showmanship, which is very costly to sustain, can be reduced. They’ll have fashion shows, but you don’t have to pay $25 million salaries.

FP: Was the money there in the end?

GT: For the multinationals? Without any doubt.

Jay Ruttenberg is editor of the comedy journal The Lowbrow Reader and its book, The Lowbrow Reader Reader(Drag City, 2012). His work has appeared in The New York Times, Details, Spin, and Flaunt.