Fashion Thinking: Creative Approaches to the Design Process

/On occasion of her new book on fashion design education, Fashion Thinking: Creative Approaches to the Design Process (AVA, February 2013), Fiona Dieffenbacher--director of the BFA in Fashion Design at Parsons the New School for Design--reflects on new and exciting approaches to fashion education:

by Fiona Dieffenbacher

The main question to be asked of fashion education today is “Are we training students to design clothes or to create fashion?” To be makers, creators, or both?” At Parsons The New School for Design we have re-approached our curriculum to address these questions, which has led to innovative, new pathways for our students to develop as designers.

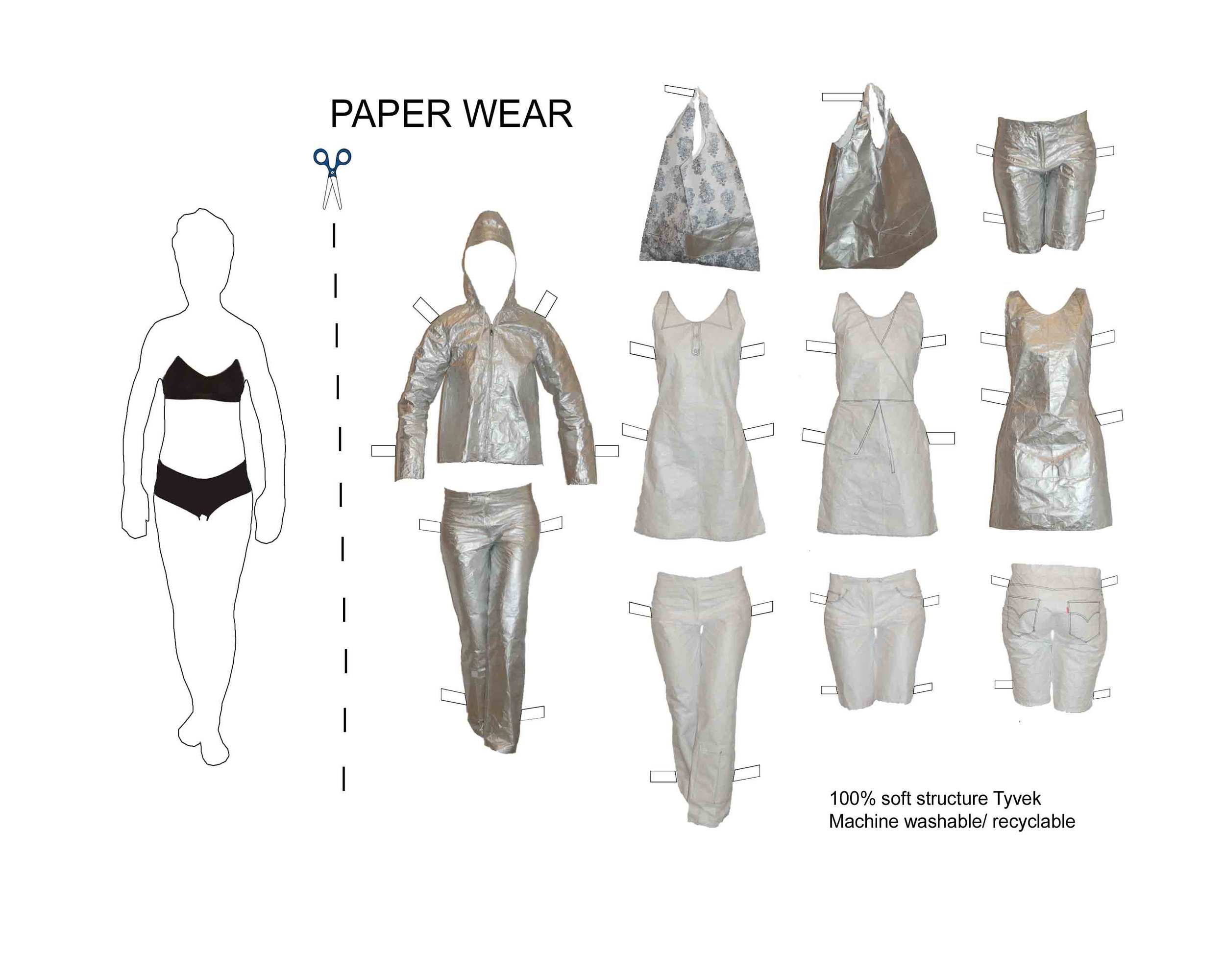

In order to understand the difference between the spheres of making and creating fashion, we have focused on design thinking as a method of envisioning a reality that does not yet exist, and as a means for achieving innovation. Fashion thinking involves harnessing the vast array of skills at the designer’s disposal, while embracing the chaos of the process itself. This might include upending traditional approaches or reapporpriating them to unearth new ways of creating and making clothes.

“Fashion Thinking: Creative Approaches to the Design Process” highlights the work of nine students, documenting their responses to a variety of design briefs and their process: from idea to concept and design. These projects demonstrate that there are multiple entry points into that process and a million ways out. In between there are some consistent doors that each designer will go through (albeit in varying orders) and there are consistent tools they will utilize to accomplish the end result, but the rest is up for grabs. Emerging designers must learn to develop both their own personal philosophy of design and a particular way of working, which involves taking ownership of the process itself.

Traditionally, fashion design texts have tended to suggest a “one-size-fits-all” approach to the design process: research – sketch – flat-pattern – drape – fabrication – make. While this order works for many designers, and are essential building blocks of the design process, this does not work for all. At Parsons we have developed a curriculum that encourages a variety of approaches to design versus heralding a formulaic method. If we persist in training fashion students to design via a process that is rote and mundane, we have missed the point entirely.

Not everyone begins with a sketch; indeed some don’t sketch at all. Isabel Toledo is one such example, “I don’t start new things at the sketch pad or the drawing board. For me, fashion design begins at the sewing machine and the pattern-making table. I know that I am creating a design when I make things with my hands, giving them form and shape, often inventing new techniques to fold and manipulate cloth as I experiment with my designs and perfect them over time.”[1]

Dissatisfaction with a particular way of working can also lead to a breakthrough in the design process and this was true for Rei Kawakubo, two years before her first presentation in Paris in 1979. “I decided to start from zero, from nothing, to do things that have not been done before, things with a strong image.” Speaking of her decision, Harold Koda commented on her process, “…‘to start from zero’… has become a constant of her design process. Season after season, collection after collection, Kawakubo obliterates her past… Liberated from the rules of construction, she pursues her essentially intuitive and reactive solutions, which often result in forms that violate the very fundamentals of apparel.”[2]

In the BFA Fashion Design program here at Parsons, we have witnessed a distinct shift away from a right/wrong philosophy of teaching toward a more problem-based approach to learning. A student-centric model now exists where the fundamentals of design, construction, digital and drawing are taught in tandem with a full roster of studio electives and liberal arts that students select from a wide variety of options open to them across our university, The New School. Students learn traditional techniques and immediately apply them within the context of their own approach to design. In doing so they begin to articulate their own aesthetic and visual vocabulary from the outset of their experience in the program. Additionally, students are now encouraged to develop a central body of work that is re-contextualized across their suite of electives, which informs their work in new ways.

There is no “right” way to approach design; there are no “wrong” turns. Everything matters. Designers are problem-solvers and problems present challenges that often lead to creative solutions that could not have been conceived of any other way. Within the unpredictability of the process ‘mistakes’ transform into new ideas, yielding fresh concepts that drive silhouette and form forward. Innovation happens on the heels of error in the midst of chaos and complexity.

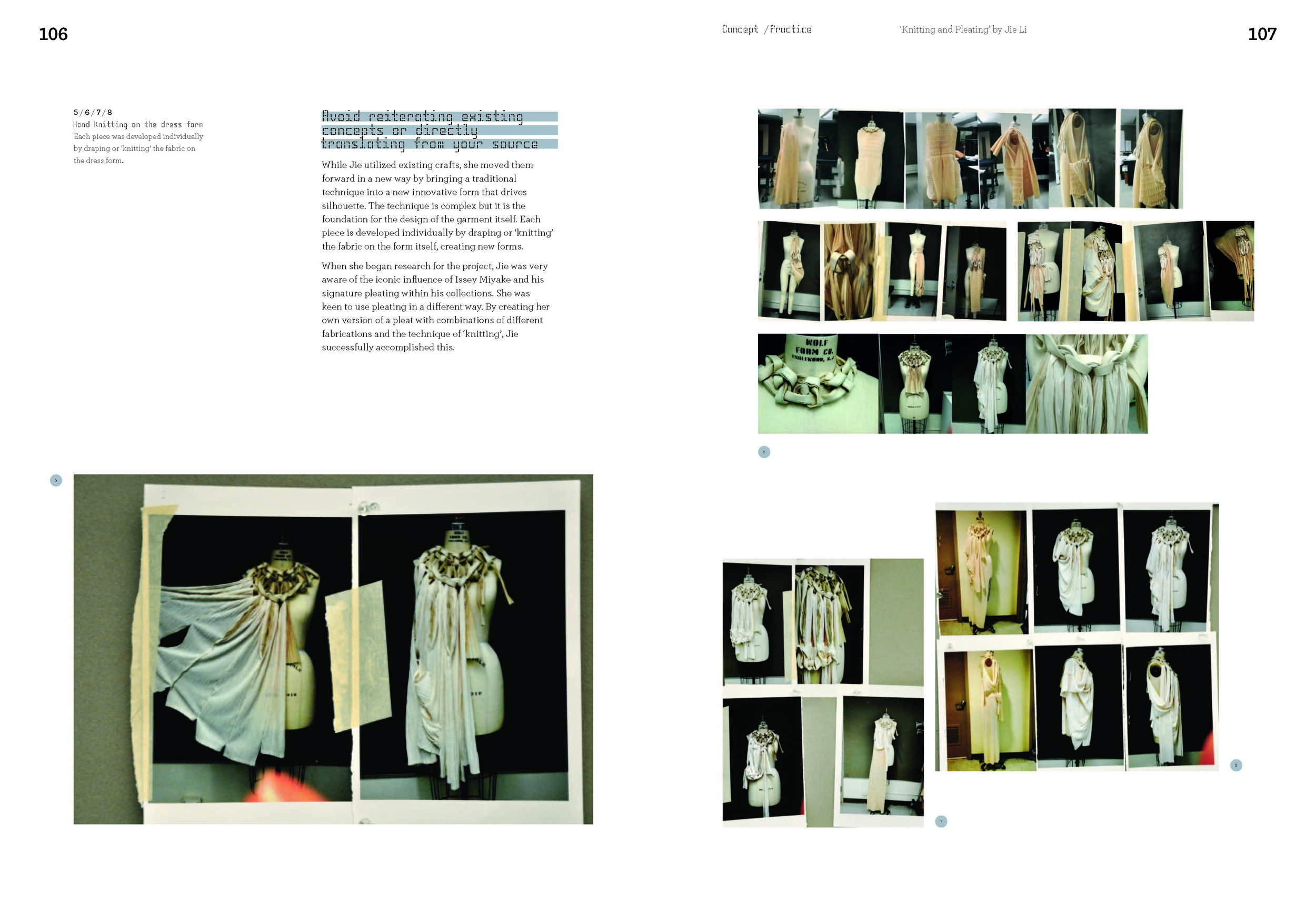

Jie Li, "Knitting and Pleating".

[1] “Roots of Style, Weaving Together Life, Love, and Fashion” by Isabel Toledo

[2] “ReFusing Fashion: Rei Kawakubo,” MOCAD [Museum of Contemporary Art], Detroit, Exhibition catalogue, March 2008

Fiona Dieffenbacher is Assistant Professor and Director of the BFA Fashion Design program at Parsons The New School for Design. An alumna of the program, Dieffenbacher has served as a faculty member since 2005. Prior to being appointed director of the BFA program, she served as the director of external partnerships for the School of Fashion, where she oversaw projects with Coach, Louis Vuitton, MCM, Swarovski, LVMH and others. In her current role, Dieffenbacher has led the program though the development and implementation of a new curriculum. Dieffenbacherholds an undergraduate degree in Fashion and Textiles from the University of Ulster in the UK. At Parsons, she was the recipient of a Designer of The Year Award (1993). In 1998, she launched a ready-to-wear label Fiona Walker, which was shown at Mercedes Benz Fashion Week and sold at select retailers in the U.S and internationally. The collection was featured in WWD, The New York Times, New York Magazine, Harpers Bazaar, Lucky, and Cosmopolitan