Among the noteworthy films featured this year at the New York African Film Festival at Lincoln Center was George Amponsah and Cosima Spender’s documentary, The Importance of Being Elegant, which examines the Congolese subculture centered around the worship of clothes (kitende) known as la Société des ambianceurs et personnes élégantes (the Society of Revelers and Elegant People), or in short, la Sape. The film follows internationally renowned Congolese soukous musician, Papa Wemba (né Jules Shungu Wembadio Pene Kikumba) and his coterie of expatriate Congolese supporters in Paris and Brussels shortly after his release on bail in 2003 on charges of importing 350 illegal immigrants (at a little over US$4000 per person) to pose as members of his band. Beset with legal fees and an impending criminal trial, Papa Wemba records a new album and prepares to launch an extravagant concert in Paris to try to piece his life back together and uphold his central position in the expatriate Congolese community. In the meantime, young immigrant Congolese in Paris and Brussels who embrace the sapeur lifestyle, ‘battle’ each other for the title of “Parisien”—the equivalent of an exceedingly stylish man—by flashing their labels in ritual dances in night clubs and mounting challenges through preening displays of label versus label. They also pay an exorbitant price for a “dedication” or the singing of their names by Wemba into his new album.

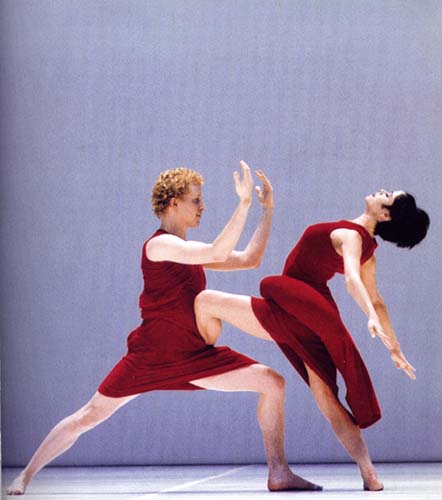

Still showing Papa Wemba and his Cavalli fur coat (courtesy of NYAFF)

As the quintessential king of the sapeurs, Papa Wemba found commercial success in the 1970s through the innovative style of fusing traditional Congolese rumba with Western pop and rock influences. His new found critical acclaim became his ticket out of his native Zaire. Along with a number of other Lingala musical superstars, Papa Wemba started a new life abroad in Paris, touring Japan and the US via Europe with Peter Gabriel, and returning home to Kinshasa occasionally to perform for his doting fans. Dressed in expensive designer labels, Papa Wemba elevated style to a form of religion, replete with high priests, archbishops, popes, and even saints (in this case, Cavalli, Versace, Gautier, Burberry, Comme de Garçons, Yamamoto, Miyake, and Watanabe). His worship of designer labels (or griffes) and the musical lyrics which praise them, entice impoverished Congolese young men to take the oneiric pilgrimage to France and Belgium to acquire designer clothes, and eventually to return home with the hopes of an improved social standing. The turbulent political and socio-economic history of the Democratic Republic of the Congo with its widespread poverty and 5.4 million excess deaths from the Second Congo War, sets a brutally sardonic backdrop for these young men who desire to escape from the harsh realities of Kinshasa only to end up enduring an increasingly harsh existence when they reach the streets of Château Rouge in Paris or the district of Ixelles in Brussels. Often without the legal documents to stay in the country, the sapeurs beg, steal, and hustle (although the specifics of these illicit activities remain ambiguous in the film) for money to be able to afford the designer clothes to keep up with Papa Wemba’s fashion ideology. In the documentary, one such sapeur named the “Archbishop” attempts to establish a name for himself in the Parisian Sape scene only to later come to the realization that the extravagant and flamboyant lifestyle has been nothing more than an illusion.

Watching this documentary, it’s unavoidable to draw parallels to the image of ‘bling-bling’ culture propagated by new school hip hop. The projection of cool by emulating the conspicuous consumption of elites, and the impersonation of success and fashionability, rather than the projection of a sense of depravation are traits shared by both subcultures. Indeed, Amponsah and Spender seem more inclined to portray the phenomenon of la Sape in a similar vein to the glorification of material excess found in hip hop culture. The inherent paradoxes of poor unemployed urban youths who hustle to be able to wear designer duds or footage of Papa Wemba trying on garish fur coats by Cavalli, all seem to confirm this. Yet, la Sape has a history that is far older than this documentary suggests. Originating in Congo-Brazzaville in the 1930s, the movement’s inspiration (though often disputed) draws reference from the archetypal dandies of modernity as well as Western films of the 1940s and 1950s, especially those of mobster, black and white thrillers, and the Three Musketeers. The sapeurs of Brazzaville were mainly composed of lower middle class young men, high school drop outs, and later, disenfranchised youths. Observing a strict three color rule, their austere elegance became a method to cope with colonialist hegemony and assimilation policies, as well as a way of subversion and resistance. In addition, the acronym la Sape plays on the French term for clothing and points to the fascination with their colonizers. The sapeurs of Brazzaville preached a conservative style that focused on cleanliness and absence from using hard drugs. Through the cultivation of clothes, they sought to define their social distinctiveness while deriving pleasure in admiring themselves, somewhat akin to what Pierre Bourdieu has called a ‘strategy of self-representation’. Fashion became a symbolic gesture of reclaiming power in times of economic deprivation and attempts at political dominance. In some instances, it proved a man could be a master of his own fate. Some authors have remarked that the sapeurs concealed their social failure through the presentation of self and the transformation of it into an apparent victory.