Interview with Curator Thierry-Maxime Lori

/by Ingrid Mida

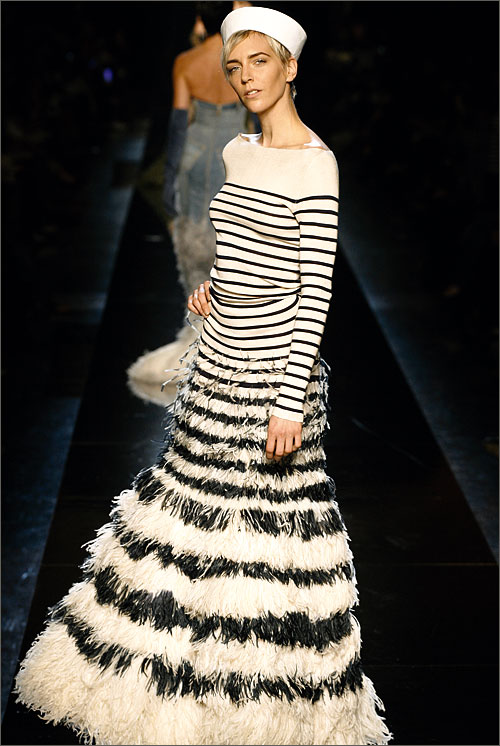

The Fashion World of Jean Paul Gaultier (Photo courtesy of the MMFA)

Thierry-Maxime Loriot curated the exhibition The Fashion World of Jean Paul Gaultier which opened recently at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Loriot joined the Museum in 2008 as a research assistant and in 2009 assisted Guest Curator Emma Lavigne with the exhibition Imagine: The Peace Ballad of John & Yoko. Prior to joining the museum, Loriot was a fashion model who walked pret-a-porter fashion shows in New York, Milan and Paris and worked with leading photographers like Mario Testino. His extensive knowledge of the international fashion scene led Nathalie Bondil, the MMFA Director and Chief Curator to invite him to curate the exhibition The Fashion World of Jean Paul Gaultier. Loriot also edited the exhibition catalogue.

Ingrid Mida: Gaultier has been quoted as saying that “Fashion is not art.” How does this reconcile with the fact that his work is being presented as art within the Musee des Beaux Art? Do you see fashion as art?

Thierry-Maxime Loriot: Fashion can be art if we speak about a corpus like the one of Jean Paul Gaultier. As Andy Warhol said ; "With Yves Saint Laurent, Gaultier is the only one to really make art with clothes, to see clothes as a whole, by the way they assemble them". I think coming from Warhol, it is a very strong statement. When you see the craftsmanship and all the work and how imaginative Gaultier is, I consider him a real artist. He designed more than 150 collections forhimself, 15 for Hermès, countless collaborations with movie directors from Peter Greenaway to Luc Besson, dance choreographers, pop stars and all the videos he collaborated on, no other designer has ever achieved that much, but what is most fascinating is that it is always innovative, always new, never boring, which is exceptional. He iniates the trends rather than following them, which explains why he is still here after 35 years and dressing the new generation of Lady Gaga, Beyoncé and Rihanna…He has also influenced some very important contemporary artists like Cindy Sherman, David LaChapelle, Erwin Wurm and Pierre & Gilles to name a few.

The Fashion World of Jean Paul Gaultier (Photo courtesy of the MMFA)

Ingrid: Gaultier has been acknowledged for celebrating alternative beauty and incorporating models of larger sizes into his runway shows. Although there were models of different ethnicities and genders included in the show, I did not see any plus size mannequins or mannequins that appeared to be older. Was this a conscious decision based on cost?

Thierry: We are very lucky to have the collaboration of Jolicoeur International who created all the mannequins in the exhibition. Gaultier wanted to show different skin tones and recreate them. As for plus size models, Gaultier often offered the clothes to the models after the show because they were made to measure for them like Stella Ellis and Velvet d’Amour. We can see the fashion shows they were in at the exhibition. We have translated this inclusion of everyone, of mixing genders, cultures and sizes through video clips when the clothes were not available. Also, to show underwear on a plus-size mannequin would not have been the best display, because it always looks better on a real human. You can understand Gaultier’s strong social message when you see that he gave power to women by giving them the choice to wear a corset, and by giving the skirt and haute couture to men, all the while mixing cultures and paying tribute to different religions, which shows how generous and open minded his fashion is.

Ingrid: In choosing items to display from 35 years of work, was there something that you wished you could have included but had to leave out?

Thierry: Luckily no! It was a challenge to choose from all the archives and of course, to make a selection and a final choice. The final selection was donewith Gaultier, because it was very important to have feedback from him as the exhibiton is not a retrospective rather more of a contemporary installation. I had the unique chance to work with a living artist who shared with me his intentions behind his work, thus avoiding misinterpretation. He was very generous with spending days and days working with me. Though quite busy with other projects, he always approached the exhibition at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts with a smile, answering my millions of questions about his work, techniques, andinfluences. As he said, it is the biggest fashion show and collection he ever did! The exhibition had to reflect his personality, and from the comments we have heard since the opening, I think we succeeded !

Ingrid: I understand that you have worked as a model yourself. Do you think that this influences your work as a curator?

Thierry: Probably. Coming from the fashion world was a very positive experience that gave me the opportunity to refect this world from the inside and to meet so many incredible people. I included some prints from great photographers that I have worked with when I was a model and who I admired a lot like Mario Testino, Peter Lindbergh, Ellen Von Unwerth, Nathaniel Goldberg and MaxAbadian, but also other great masters like Richard Avedon, Inez Van Lamsweerde and Vinoodh Matadin, Mert Alas and Marcus Piggott, Steven Klein, Steven Meisel... Fashion is about image, and some of the most iconic images on view are by Paolo Roversi. Fashion photography translates very well what the clothes are about yet, it is rarely shown to the general public, and I wanted to show also how fashion photographers from different generations, from Helmut Newton to Miles Aldridge, have been influenced by Gaultier’s work.

Ingrid: What is your favourite garment or aspect of the display?

Thierry: I love all the galleries for different reasons. This exhibition is not a classic fashion exhibition. It had to reflect the sense of humour of Gaultier, but also his creative genius. I love the Boudoir with the corset in the padded satin box, which contains all the different corsets but also the two iconic ones on view worn by Madonna for the Blond Ambition Tour in 1990. One piece also that is spectacular is the leopard « skin » dress from the haute couture collection Russia (FW 97-98), which is a trompe-l’œil, made of glassbeads with the claws made of strass, which took more than 1060 hours to create. Extraordinary pieces like this can create the same emotion as seeing a sculpture or a painting. This exhibition presents a very unique chance to view each piece up close, especially with regard to haute couture dresses that for most have never been exhibited and shown to the public, thus providing premier backstage access to the virtuosity and savoir-faire of Paris haute couture.

Ingrid: After hearing you, Nathalie, and Jean Paul Gaultier speak at the press conference, I had a deeper appreciation for the underlying humanist message that there was no singular standard of beauty. However, I'm not sure that this important message will be evident to visitors because they are entranced by the beauty of the gowns, the animated mannequins and the cacophony of sounds, lights and action. How do you see think this message is conveyed within the exhibition?

Thierry: When you discover Gaultier's universe, you realize how open and generous his fashion is. He invented and surely broke taboos and barriers through gender-bending as reflected in the images of Tanel and the men’s skirt, but also empowered and gave freedom to a liberated contemporary womanin control of her life and her sexuality. This is shown of course through Jean Paul Gaultier's collaborations with Madonna, but is also quite evident when you see Helen Mirren in "The Cook, the Thief, his Wife & her Lover" or in his shows that feature women wearing corsets or revealing clothes. Of particular note are the animated mannequins by UBU, because the casting shows real people of different origins, and ages spanning 18 to 65, thus reflecting a very diverse crowd, a mirror of society, the society in which we live. Old, young, along with different beauties from different countries are all part of the fashion world of Jean Paul Gaultier.

Ingrid Mida is an artist, writer and researcher based in Toronto who is inspired by the intersection of fashion and art. She lectures about fashion and art and will be the keynote speaker at the Costume Society of America mid-west conference in the fall.